1 What is Cognition?

1.1 Instances of Cognition

What is cognition and how does it work? The book is titled “Instances of Cognition” to alert you to the diversity of ideas, approaches, and interests in cognition. We will also learn later that there are instance theories of cognition (Jamieson et al., 2022, readcube link to read the paper online https://rdcu.be/cGGzW). So, although research into cognition has been ongoing across centuries and much knowledge has been generated, there are many perspectives and unresolved issues that prevent widely agreed upon answers to questions about what cognition is and how it works.

The diversity of approaches and perspectives in cognition makes it difficult to provide a coherent survey of the entire field in the form of a textbook. So, this textbook adopts a museum metaphor to help provide some structure to the overview. Consider the task of learning about everything in a museum like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It’s an impossible task. The MET is way too big to see in one day. It has many rooms with countless artifacts, each with their own histories. A tour guide takes you on a path through the museum while providing context and background and highlighting interesting tidbits. However, a comprehensive understanding of the story behind a single artifact could require years or lifetimes of careful investigation.

Cognition is like the museum. It contains many artifacts in the form of questions, methods, findings, theories, applications, and implications for society. This textbook is like a museum tour guide. It is intended to highlight different domains in cognition, and hopefully find ways to tell compelling stories along the way. Like the MET is open to the public, much of the research we will discuss is open to you, in the form of published journal articles and books.

1.2 Questions of cognition

Let’s tackle two different sorts of questions. First, what is cognition? Second, what kinds of questions about cognition are researchers asking and seeking answers to?

1.2.1 Defining Cognition

An everyday definition of cognition involves anything to do with how your mind works. We will explore cognition from this everyday perspective, and from the more formal angles of the cognitive sciences.

I previously credited Neisser with coining the term “Cognitive Psychology” in 1967; however, Thomas V. Moore published a lesser known textbook called “Cognitive Psychology” in 1939 (Moore, 1939). Thanks to a twitter thread by Steve Most for pointing this out, and see Surprenant & Neath (1997) for a review of Moore’s ideas.

Ulric Neisser is credited with popularizing “Cognitive Psychology” in his 1967 textbook of the same name (Neisser, 1967). He defined cognition as:

“…all processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used”.

Neisser’s definition of cognition remains current in many respects, but is also somewhat limited to a particular information processing view of cognition (discussed in a later chapter). Neisser also had an expansive view of what cognitive research could accomplish. Here is another Neisser quote:

“If X is an interesting or socially important aspect of memory, then psychologists have hardly ever studied X”. (“Remembering the Father of Cognitive Psychology,” 2012)

Neisser’s criticism also remains current. Among the rooms of the cognitive museum, we will encounter examples of research that Neisser might have criticized for being uninteresting or not socially important. And, even though a great deal of research has been conducted, many interesting and socially relevant aspects of cognition remain under investigated. In other words, there are rooms in the museum that have not received very much research, and whole wings that could exist but haven’t been built yet.

1.2.2 Research questions

If you have ever wondered about your mind, then you probably asked a question that cognitive science is interested in answering. Cognitive research can be viewed as a growing list of topics and questions about how cognitive abilities work. To give concrete examples, the next paragraph is a list of questions about cognition.

How do you remember what you ate for breakfast? How do you remember something that happened when you were a kid? How do you learn a language? How do you know how to say a sentence? How do you think your next thought? How do you imagine things? How do you learn new skills, like walking, riding a bike, playing a musical instrument, playing a sport, or a game? How do you learn new information, and how can you study more efficiently? How do you recognize peoples faces? How do you know a tree is a tree and not some other object? How do you make plans for the future? Do you have an inner voice and if so how do you use it? How do you make decisions in your daily life? What makes you prefer some music and not others? How do you control all of your body movements, from moving your fingers to subtle facial expressions? How do you pay attention to some things while ignoring others? Why are some thing easy to forget and others hard to forget? How do you learn to read? How do you know the meaning of words? Can you train your brain to get better at something? How many memories can a person have? What does it mean to be smart? Can anyone learn anything to a high degree of skill? How do all of these cognitive abilities develop over the lifespan? How do people understand their own cognition? How do people understand other people’s cognition? What about non-human animals, what kind of cognitive abilities do they have?

This was a short list of questions, and there are room for many more. Most of them were how questions, and how questions are about explaining how things work. One of the goals of asking research questions about cognitive abilities is to generate explanations about how the abilities work. The process of generating working explanations involves a research cycle. The research cycle uses a variety of research methods to generate insight into the questions by establishing new findings and testing potential explanations of the cognitive abilities under examination.

1.3 Methods

This textbook will mostly survey experimental or quasi-experimental research methods used to ask questions about cognition. This section discusses research methods in general, in the form of the research cycle, and some examples of measurement techniques commonly employed in cognitive research.

1.3.1 Research Cycle

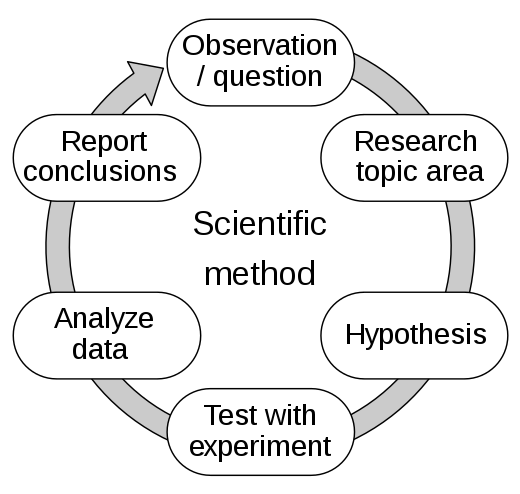

The research cycle involves a variety of methods–such as the scientific method– used to generate knowledge about cognition. The research process is represented as a cycle because the final outputs of a research project often fuel the inputs of the next project. In general, the process of generating knowledge from the research cycle is incremental and involves many iterations, repetitions, and revisions.

A researcher today might begin with an observation–like, why are some tastes delicious and others repulsive– or, a question– like, how can someone learn to read faster? Given that cognition has already been studied for well over a hundred years, a next step is often to review any existing literature on the topic or question. Literature reviews involve finding and then reading primary research articles that have asked similar questions. There are several internet search engines for primary research, such as Google Scholar or Semantic Scholar.

Prior research can often help you understand the current state of knowledge about a question. For example, if you want to read a book faster, then it would be helpful to read the review article, “So Much to Read, So Little Time, How Do We Read, and Can Speed Reading Help? (Rayner et al., 2016). This article covers many important previous results in the reading literature. Unfortunately, there is no known simple and easy method to dramatically improve reading speed without also sacrificing comprehension.

After a researcher has familiarized themselves with the previous literature, they may come up with new ideas, questions, or hypotheses. For example, maybe vision-based reading speed could be improved if fonts for text were redesigned to make visual processing faster. Ideally, hypotheses should have testable implications that can be measured.

Next, the hypothesis is put to a test with an experiment. The purpose of the experiment is to create a controlled situation where aspects of the hypothesis are manipulated to determine whether they influence the measurements. For example, a researcher might create two kinds of fonts, some fonts could be presented in bold, and other fonts could be presented in italics. Then, people could volunteer to read words presented in both fonts, and the researcher could measure reading speed.

The experiment generates measurements in the form of data that is collected under different experimental conditions. A next stage in the cycle is to analyze the data, and determine whether the manipulations had any influences. For example, if font type reliably influences reading speed, then the data should show that reading speeds are reliably slow for some fonts, and reliably faster for others.

The research cycle ideally involves a community of peers, so the final stage of a research project could be to report conclusions, or otherwise communicate the results of your research. This is typically done by writing up a research report and submitting it for peer-review to a journal. The peer-review process can help identify areas of improvement that the researcher may address in a revision. If the journal accepts the paper, then it becomes a part of the literature on that subject.

The research cycle is a process of figuring out what facts about cognition are real and in need of explanation, and then coming up with theories that explain the facts. The research cycle can be used to test claims, which can lead researchers to discover new facts and create new theories (i.e., a cyclical process). Last, cognition research is a human activity that is embedded within a socio-historical context. The discoveries of cognitive research can have applications in society (for better and worse), and the potential prospects of these applications can in turn influence the research process by guiding researchers to spend their time on some problems as opposed to others.

1.3.2 Experiments and measurements

Cognitive research often involves formal experiments and controlled measurements. This textbook assumes you may be unfamiliar with aspects of experimental methods in psychology. We will cover important experimental details when necessary throughout the textbook.

Experiments are used to manipulate an independent variable (like type of font) and measure the influence (or lack of influence) on a dependent variable (like reading time). If the experiment is properly controlled and free from confounding variables, then experiments showing positive results suggest a causal connection between the manipulation and the change in the measurement. There are an enormous number of experimental procedures, manipulations, and measurements specifically designed to answer questions about cognition.

In some research domains the objects of inquiry can be measured directly. For example, geologists can measure rock formations, biologists can inspect cells with a microscope, and neuroscientists can measure action potentials of single neurons. In cognition, the objects of inquiry are often cognitive processes that can not be measured directly. Instead, inferences about cognitive processes are made from indirect measurements.

Consider your ability to form thoughts, and more specifically your ability to generate examples from a category. For example, how many names of mammals can you write down in 5 minutes? Your ability to generate many mammal names is assumed to be driven by cognitive processes involved in language, semantics, categorization, memory, thinking, motor movements, and more that are instantiated in a complex network of physical and physiological processes. As a result, the cognitive processes involved in something as simple as thinking of animal names are complex and not easy to directly measure. Instead, a behavioral measure of task performance is directly observable, and is used to make inferences about the cognitive processes producing the behavior. For example, a behavioral measures could be the number of animals someone wrote down, how long it took to write each name down, and even patterns like the order and grouping of how the names were written down.

In general, measurements in cognition are taken while a participant is performing a task. Measurements are often behavioral aspects of task performance, but may involve measures of physiological processes like heart rate, or brain processes as well. Common behavioral measurements include accuracy and reaction times to complete actions or portions of a task. Technology like eye-trackers can measure eye-movements during task performance; or systems like the X-box Kinect can be used to measure body motion. People are often asked to make judgments on various rating scales, and generate or produce information like words or drawings. Common physiological measurements include heart rate, skin-conductance, and pupil-dilation, which sometimes correlates with cognitive activities. Common non-invasive neuro-physiological techniques include EEG, fMRI, MEG, and PET, for measuring correlated brain activity during task performance.

Finally, the development of measurement tools can be a creative process. A personal favorite of clever tool development is from Patrick Rabbitt, who was investigating the skill of typewriting on mechanical typewriters (Rabbitt, 1978). He wondered whether typists might hit keys more softly when they make errors, perhaps because they knew they were making an error, and were trying to stop the keystroke. The clever bit was how to measure response force without creating a special typewriter capable of measuring forces for individual key-presses. Rabbitt had typists type on layers of carbon paper using a mechanical typewriter. With this apparatus harder keystrokes would impress on deeper layers of the carbon paper, while softer keystrokes would only impress faintly on shallower layers. Rabbitt did find evidence that typists pressed keys more softly when they were making some errors. This is an example of a finding or phenomena which we discuss next.

1.4 Findings, effects, and Phenomena

The research cycle in cognition has produced numerous findings, effects, and phenomena. A finding refers very generally to results from the research cycle. For example, Rabbitt found that typists press keys a little bit more softly for some of the errors that they committed. Another general word for finding is observation, and we could say that Rabbitt observed soft responses during error production in his study. I’ll reserve the word effect for findings that are the result of an experimental manipulation, especially where the manipulation has an effect on the measurement. Finally, phenomena refers to classes of related findings or effects.

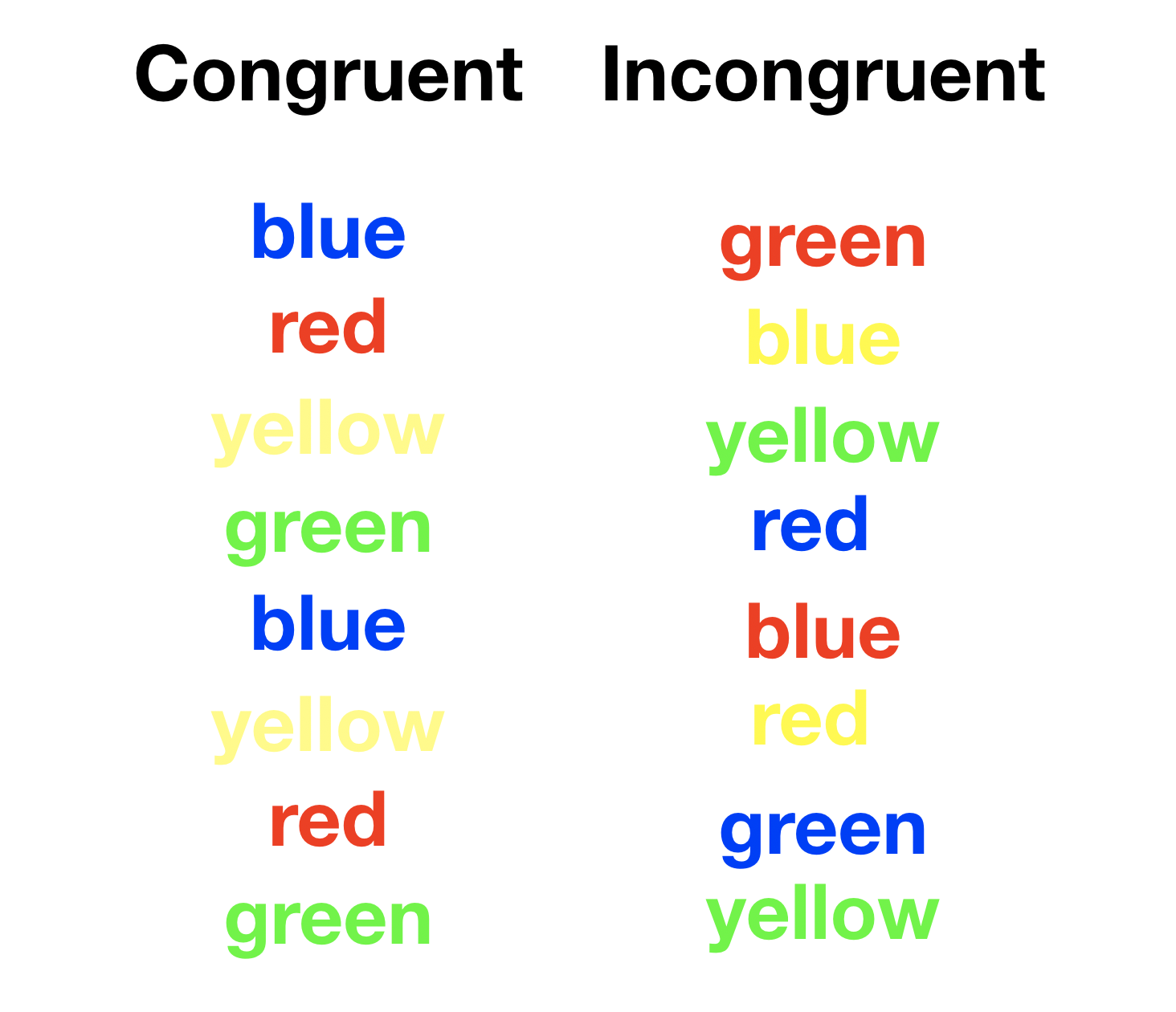

The Stroop effect (Stroop, 1935) provides a useful example. In a Stroop task, subjects are shown stimuli like in the example to the right, and asked to name the ink-color of the stimulus on each trial. For congruent stimuli, the ink-color matches the name of the word, like the color blue in the word BLUE. The correct answer for this stimulus is blue. For incongruent stimuli, the ink-color does not match the name of the word, like color red in the word GREEN. The correct answer for this stimulus is red. The typical finding is that participants are faster and more accurate to identify congruent than incongruent stimuli. This difference is termed the Stroop effect 1, which refers to the effect of the congruency manipulation on the reaction time or accuracy measure. Stroop effects can be obtained with many different combinations of stimuli that involve manipulations of matching and mismatching target and distractor dimensions, they have been the subject of many investigations, and are collectively referred to as Stroop phenomena 2.

There are too many findings in cognition to discuss in a single book. This textbook aims mostly for breadth to give readers a high level overview of many findings and phenomena. On occasion we also inspect particular findings and phenomena with additional depth to examine how experiments are used to evaluate process-based explanations of findings and phenomena.

1.5 Explanations, Theories, and Models

Just like we will encounter numerous findings and phenomena across many domains in cognition, we will visit almost as many theories, models and general approaches to explaining those phenomena. There is no single agreed upon format for theories or models, so explanations take a variety of formats, from informal verbal theories to formal mathematical models. Explanations can also be aimed at different levels of analysis, and they are often metaphorical in nature.

One of the problems with explaining how cognition works is that cognitive systems– like people and animals– are extremely complex and made up of many interacting physical parts. The complexity makes a reductionist account of cognition very challenging because there are so many parts and pieces of parts to explain. For example, a reductionist theory might attempt to explain a cognitive phenomena like human memory in terms of the operation of physiological substrates in the brain, which would require an explanation of how neuronal processes work at an electrical and biological level, which would require explanations in terms of physics and chemistry and so on. Physiological accounts of cognitive phenomena are one standard for reductive explanation, but there are others as well.

1.5.1 Levels of Analysis

Another approach to explanation in cognition invokes the concept of multiple levels of analysis Pylyshyn (1984). For example, vision scientist David Marr described three levels of analysis for the task of explaining visual perception from a computational perspective.

Consider first that vision involves a series of transformations beginning at the moment where light hits the retina. From here, photo-receptors in your eyes convert light into electrical impulses sent through the optic nerve, past the optic chiasm, where they are received by neurons in the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus, which is further connected to primary visual areas at the back of the brain. Somehow the visual processing pathways of the brain turn patterns of light falling on the retina into perceptions. Marr considered this system from a computational perspective involving three levels of analysis 3.

Marr’s likened visual processing to information processing in a computer system, and suggested that both should be understood in terms of three levels of analysis: computational, representational or algorithmic, implementational or hardware.

1.5.1.1 Computational Level

The computational level refers to the overall goal of a process. For example, what is the computational purpose of an eyeball? At this level, and in the context of the rest of the visual system, the goal of eyeballs could be to transduce light photons into electrical signals for further processing. At the computational level it is possible for the goal to be realizable in multiple ways. For example, smart phones with digital cameras also have a lens system to convert photons into electrical signals. So, if you were to imagine yourself as an alien researcher wondering about eyeballs or digital camera lens, one level of explanation involves understanding the purpose or goal of the system, which in this case would be to capture and convert light for further processing.

1.5.1.2 Representational or Algorithmic Level

The representational or algorithmic level refers to the steps taken to achieve the computational goal. For example, you might have the goal (computational level) of making chocolate chip cookies. The ingredients and steps in the recipe is a good example of the representational or algorithmic level of analysis. The representations refer to the inputs and outputs of the process, such as the raw ingredient inputs, and the cookie outputs. The algorithm refers to the step-by-step instructions for transforming the inputs to the output. A good recipe for making chocolate chips contains a reasonably precise high-level description of the ingredient list (representations), and the combination and cooking instructions (algorithm) to create tasty cookies.

To return to the domain of vision, photons are the representational inputs of eyeballs and digital cameras. The algorithm in either system refers to the steps, or way in which, the inputs are transformed into the electrical signals as outputs.

1.5.1.3 Hardware implementation level

The hardware implementation level refers to how the representations and algorithm used to accomplish a computational goal are instantiated in a physical system. For example, what specific physical elements and processes enable an eyeball to transduce light into electrical signals? Similarly, what specific physical elements and processes enable a digital camera to capture images and store them in computer memory?

1.5.1.4 Summary

Using Marr’s levels as a guide, this textbook will mostly focus on computational and algorithmic levels, rather than on the hardware implementation level. If you are a student at Brooklyn College taking this introductory course in cognitive psychology, you will find more elaboration on brain mechanisms supporting cognition in other courses such as Mind, Brain and Behavior.

1.5.2 Metaphorical Models

Metaphorical models are also common strategies for explanation in cognition. Metaphorical models refer to the process of mapping a simple model system as a metaphor for describing and understanding another more complicated system. For example, horse-racing has been used as a model for explaining the Stroop effect. The basic idea is that word and color (or target and distractor) information compete for identification, just like horses running down a track compete to get across a finish line. The metaphor does not assume that people have horses or a race-track in their brains. Instead, the metaphor provides terms and functional relationships that can provide well-fitting descriptions of Stroop phenomena, and even make predictions about what might happen to the effect under different experimental manipulations. Metaphorical models can be informal and verbal, like how I have just loosely described stimulus identification in terms of a horse-race; and, they can be more formal and mathematical. We devote a whole chapter to computational theories to provide some more detailed examples of formal theorizing in cognition.

1.6 Applications

To simplify some of the preceding discussion up to this point, the research cycle in cognition produces theory and phenomena, which can lead to new applications and technology in the real world. For example, theory about how people learn skills could be used to modify training curriculum and enhance the skill-learning process. Many applications have already sprouted from individual domains in cognition, and these will be highlighted in the upcoming chapters.

1.7 Implications

Cognitive research spans a few centuries and has already produced many theories, findings, and applications. However, cognitive research has not always had uniformly positive implications for society, and there are examples where research applications negatively impacted specific groups of people (Prather et al., 2022). Issues of equality and justice are important when discussing cognitive research and its applications. To address these issues, the textbook will occasionally discuss socio-historical context around the research and researchers that we discuss. To take one example, we will examine how research on mental imagery ability and the early development of intelligence testing were influenced by the widespread eugenics movement of the time. This era of psychology made a deep impression on subsequent cognitive research, and raises important questions about how psychological research should be applied in society.

1.7.1 Questions to keep in mind as you learn about cognition

What are the goals of the cognitive sciences and research in cognitive psychology? Who has been involved in setting those goals? Are the goals useful? What kind of questions about cognition have already been asked by researchers? What were the scientific as well as social-historical reasons for why those researchers asked those questions? What answers were found, and how were they informative or not informative about how cognition works? How do the measurements and tools that researchers use to ask questions influence the kind of picture they build about how cognition works? What kinds of questions about cognition are not being asked that should be asked? Why are they not being asked? What benefits to society have been produced by the cognitive sciences? Have the benefits been spread equitably across different groups of people? What costs to society have been produced by the cognitive sciences? How are the costs shared by society? Are there injustices resulting from cognitive science research? Have they been adequately addressed? How should society decide whether or not to proceed with different kinds of research?

1.8 Reading primary research articles

Researchers produce knowledge about cognition using the research cycle and they communicate their findings in the form of primary research articles, usually published in academic journals. There are many academic journals in the domain of cognition, and you can find a list of journals on the course website.

Learning how to read, comprehend, and critically evaluate primary research articles are important skills in general; and, they are essential for engaging with the literature on cognition. There will be opportunities to read primary research throughout the course. This section provides a tutorial on how to read research articles using the QALMRI technique 4.

Here are some reasons why it is useful to improve your ability to read primary research articles.

Learn how to find scientific research that has been conducted on topics of your own interest, and then evaluate the claims and evidence for yourself.

Evaluate whether or not you should believe particular scientific claims, or claims made by the media about new “research findings”

Look at the evidence to see whether it actually provides an answer to the question that was being asked

Look at the questions to see if they are good ones, and learn how to ask better questions

Understand how theories and hypotheses work and make predictions about psychological phenomena

1.9 The QALMRI Method

QALMRI is an acronym for critical parts of research articles. It stands for Question, Alternatives, Logic, Method, Results, and Inference. This section demonstrates using QALMRI as a guide for reading a primary research article. QALMRI can also be used as an activity or assignment, and an example of a QALMRI assignment is given at the end.

1.9.1 Step one, find a paper

The first step is to find a primary research article to read. To demonstrate QALMRI, I chose a paper from my own research. The article is titled, “Warning: this keyboard will deconstruct – The role of the keyboard in skilled typewriting” (Crump & Logan, 2010). This paper was published in the journal Psychonomic Bulletin and Review in 2010 and can be freely downloaded as a pdf here.

Before continuing, I suggest you download the paper and give it a quick glance. It it is only 5 pages long.

1.9.2 Anatomy of a primary research article

The paper you just downloaded is an example of a primary research article. The pieces of a research articles are very similar. For example, this one has a title, an abstract, an introduction, methods and results sections for two experiments, a general discussion, and references. Most research papers have similar components.

Research papers are often written for a technical audience, which refers to other researchers who are already familiar with the domain. As a result, students may find it challenging to extract and comprehend major points of research articles. We will use QALMRI as an aid to help you identify and comprehend the components of a research paper.

1.9.3 Q stands for Question

Researchers ask and answer research questions. So, your first task is to identify what questions are being asked in the research article. Research questions are usually stated in the abstract or the introduction, and sometimes they are restated near the beginning of the general discussion.

You may notice many different kinds of questions being stated in a research paper. It is helpful to distinguish between broad questions and specific questions. A single research paper is rarely capable of answering very broad questions, but it may have answered a specific question.

The paper you downloaded is about cognitive abilities mediating skilled typewriting on a computer keyboard. This topic is associated with many broad questions. For example, how do people control their own body movements? How do people learn to type without thinking about what their fingers are doing? How do people learn skills? How do people learn language? All of these questions are too big for a single research paper to answer.

The paper also asks specific questions. The overarching specific question is about how the feeling of the keyboard influences typing performance. People can type on keyboards with keys, or on flat surfaces without keys. How does tactile feedback from the keyboard influence typing performance?

1.9.4 A stands for Alternatives

Experimental research in cognition is often designed to test alternative explanations or hypotheses about a cognitive ability. When reading a paper you should attempt to identify the alternative explanations or hypotheses being discussed. Note also, sometimes a paper may only discuss one alternative hypothesis. More important, the alternative or hypothesis should contain an implication that can be tested later on.

The example paper has two major alternative ideas about cognitive processes in typing behavior. Both alternatives provide ideas about how people are able to move their fingers to individual keys very quickly and accurately, even without looking at the keyboard.

One possibility is that people have an internal cognitive map of the keyboard. The cognitive map represents the location of the keys on a computer, and typists may use this internal “mind” map to direct their fingers to appropriate locations while typing. An implication of the cognitive map idea is that typists may not need to rely on the feeling or touch of a keyboard in order to type quickly and accurately. Instead, their fingers can move to each key based entirely on directions from the internal map.

An alternative possibility is that people do not use an internal map of the keyboard. Instead, people may learn associations between the finger movements required for each keystroke and they way they feel (tactile, haptic, and proprioceptive feedback). An implication of this idea is that feeling the keyboard may be an important component of typing skill, especially for typists who learned to type on keyboards with keys.

1.9.5 L stands for Logic

The logic of the alternatives or hypotheses is nearly identical to the hypotheses themselves, but more formally stated in terms of if/then statements. Here are two example logic statements for each of the alternatives discussed above:

IF typists use an internal cognitive map that does not require feedback from the keyboard to guide their fingers, THEN typing performance should not be influenced by manipulations that remove tactile feedback, such as typing on keys vs a flat surface.

IF typists use feedback from the keyboard to guide their fingers, THEN typing performance should be influenced by manipulations that remove tactile feedback, such as typing on keys vs a flat surface.

1.9.6 M stands for Method

The method refers to the tools used to answer the research questions. More specifically, the method will usually be carefully designed to test the logical implications of the alternative explanations. In experimental research, the method will involve at least one independent variable or manipulation, and at least one dependent variable or measurement.

In our example, the method involved having skilled typists copy text while they were typing on keyboards with different surfaces, that provided less and less tactile feedback. The primary manipulation had four levels, and involved changing the feeling of the keyboard: there was a regular keyboard, a rubber button keyboard, a flat surface keyboard, and a laser projection keyboard. Measurements of typing performance (keystroke typing times and accuracy) were collected for each typist as they typed words on each keyboard.

1.9.7 R stands for Results

The results are a final product of the research cycle. A given research article may present many results depending on the complexity of the method. In general, the results refer to an analysis of whether the experimental manipulation influenced the measurements.

In our example, typing performance was measured for four different keyboards. Results were reported in a graph and showing different measures of typing performance, such as reaction time (time to start typing a word), inter-keystroke interval (time between keystrokes), and error rate. The major result was that typing performance WAS influenced by the keyboard manipulation. Typists were fastest and most accurate on a regular keyboard, and always slower and less accurate on the keyboards with less tactile feedback.

1.9.8 I stands for Inferences

Inferences may be the most important product of a research project. Inferences connect the results back to the original research questions. So, what inferences about the alternative explanations under investigation can we draw based on the results of the research? Inferences are possible if the methods do a good job of testing the logic of the alternatives.

In our example, the logic of the internal keyboard map idea suggested that manipulations to the feeling of the keyboard should not influence typing performance. However, the results of the study showed that reducing tactile feedback from the keyboard causes slower and more error-prone typing. So, one inference from the study could be that typists do not rely upon an internal map of the keyboard.

1.10 Writing a QALMRI assignment

Writing a QALMRI for any research paper (one that you are writing, or one that you are reading) involves writing short answers to each of the QALMRI points using clear and concise language. It is a condensed, short-form, version of the research. Your task is to answer these questions:

Question: What was the broad question? What was the specific question?

Alternative hypotheses: What were the hypotheses?

Logic: If hypothesis 1 was true, what was the predicted outcome? What was the predicted outcome if hypothesis 2 was true?

Method: What was the experimental design?

Results: What was the pattern of data?

Inferences: What can be concluded about the hypotheses based on the data? What can be concluded about the specific and broad question? What are the next steps?

1.11 Example QALMRI

Even if you haven’t read the article, reading a QALMRI should provide you with enough information to get a basic idea of what the article was about. The following QALMRI summarizes our example article by Crump & Logan (2010) (Crump & Logan, 2010).

1.11.1 What was the broad and specific question?

The broad questions are about spatial cognition. How do people understand and represent the spatial relationships between objects in the environment? Do people have “spatial maps” in their head?

The specific question is how do typists know where the keys are on the QWERTY keyboard?

1.11.2 What are the alternatives?

Typists have an internal cognitive spatial map of the keyboard that they use to guide their fingers during typing

Typists do not have a map-like representation, instead they rely on learned associations between cues such as the feel of the keyboard to guide their fingers during typing

1.11.3 What is the logic?

If typists have an internal map of the keyboard, then they should be able to guide their fingers to correct locations based on the map alone and no feedback from the environment. For example, if we could measure “air-typing” without a keyboard, then typists should still be able to put their fingers in the correct locations even when the keyboard is missing because they are relying on their internal map.

If typists do not use an internal map of the keyboard, then their finger movements should become slow and inaccurate when they try to type without a keyboard, or in other conditions that change the normal feel of the keyboard, and thereby remove the cues that typists use to direct their fingers.

1.11.4 What is the Method?

Typists copied paragraphs in four conditions that manipulated tactile (touching) feedback from the keyboard. They typed on a normal keyboard, a keyboard with the keys removed exposing the rubber buttons underneath, a flat circuit board without, and on a flat table with a laser projection keyboard.

1.11.5 Results

Typists were fast and accurate in the normal keyboard condition. Typists were slow and inaccurate in all of the other keyboard conditions, where normal tactile feedback was removed.

1.11.6 Inference

The results are not consistent with the internal map hypothesis. If typists had an internal map, and did not rely on tactile cues, then they should have typed normally even when the cues were removed. The results are consistent with learned association hypothesis, that typists rely on cues, like the feel of the keyboard, that are associated with particular key locations.

1.12 Appendix

1.12.1 Glossary

Cognition

This textbook defines cognition as processes of mind and behavior, including human and non-human animal minds, and potentially computational minds. Examples of cognitive abilities include perceiving, attending, remembering, thinking, empathizing, deciding, predicting, judging, etc.

- Anything to do with how minds work

Dependent Variable

The measurement in an experiment. For example, in a recall memory experiment a researcher could measure memory performance by counting how many words were remembered under different experimental conditions.

Independent Variable

An experimental manipulation involving at least two levels. For example, an experiment testing the efficacy of a drug could have an experimental level where participants receive the drug, and a control level where participants do not receive the drug.

QALMRI

An acronym used an aid for reading primary research articles. QALMRI stands for Question, Alternatives, Logic, Methods, Results, and Inference. Research papers ask questions about how phenomena work, they propose alternative working explanations, and test the logical implications of those explanations with methods. The methods produce results that can be used to generate inferences about the working hypotheses and generate insight into the phenomena under investigation.

Scientific Method

A systematic process using controlled experiments and observation to generate knowledge about phenomena under investigation.

1.12.2 References

Footnotes

named after psychologist J. R. Stroop who invented the procedure↩︎

or congruency phenomena, compatibility phenomena, interference phenomena, and cognitive control phenomena↩︎

The computational view of cognition will receive much more elaboration across the textbook↩︎

Adapted from Kosslyn, S. M., & Rosenberg, R. S. (2001). Psychology: The Brain, The Person, The World. Boston: Allyn & Bacon↩︎

Reuse

Citation

@incollection{j.c.crump2021,

author = {Matthew J. C. Crump},

editor = {Matthew J. C. Crump},

title = {What Is {Cognition?}},

booktitle = {Instances of Cognition: Questions, Methods, Findings,

Explanations, Applications, and Implications},

date = {2021-09-01},

url = {https://crumplab.com/cognition/textbook},

langid = {en},

abstract = {This chapter presents an overview of the questions,

methods, findings, explanations, applications, and implications of

cognitive research in general. At the end, the components of a

research article are discussed in relation to the research process

in general, and in the form of a tutorial to develop skill and

familiarity with reading and comprehending primary research in

cognition.}

}